It was Agatha all along!

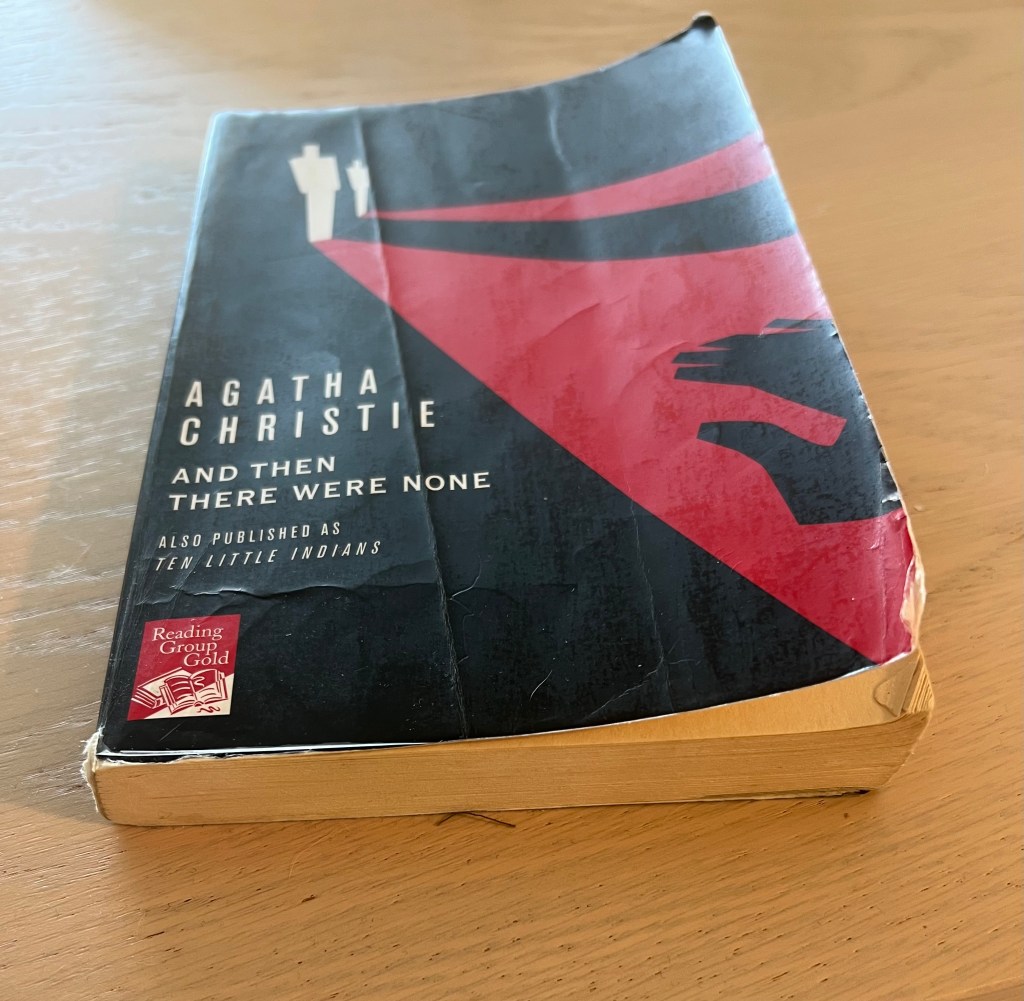

I remember when I read my very first Agatha Christie. I started strong, with And Then There Were None – to this date, still my favorite Christie, although I knew it as the more-problematic-but-not-as-problematic-as-the-real-title Ten Little Indians then. I was totally flummoxed by the ending (still am, by the way) and in awe of Christie’s powers. The red herrings! The double bluffs! The sheer audacity this woman had, in a time when many women didn’t dare have any audacity at all.

Of course, now that I’ve read some forty-odd books by Christie, the honeymoon phase has faded, but my love for her still rings true (despite an increasing awareness of the breathtaking racism she often displayed; however, I’m of the opinion we can still enjoy books with such hallmarks). Here are a few key takeaways from my journey through Christieland.

When it comes to Christie’s plot twists, mistaken identity is the name of the game.

In fact, I’d go so far as to say that this is true when it comes to nearly all plot twists. When I reflect on my favorite twisty thrillers, even those outside the CCU (Christie Cinematic Universe), the gut-punch shock nearly always comes the reveal that Someone Is Not Who They Said They Are. I don’t mean this in a vague way, like “this person is not as nice as they seemed!” I mean that there is usually some form of misleading or false identification. The brother is masquerading as the dentist. The dentist is masquerading as the brother. The dentist’s brother is masquerading as the brother’s dentist. (Does that make sense?) One of Christie’s absolute favorite devices is to have a key alibi revealed as fake because the star witness, or the star actor, was, indeed, an actor – someone dressing up as someone they weren’t to carry out their evil plan.

Actually, it’s usually the person you most suspect.

By which I mean: yes, yes, it’s the person least likely to commit the crime, in the sense that it’s the person you may be misled into not suspecting. But that very same person is usually the most obvious person to have carried out the murder. Bonus points for Christie when that person is a main character, as it’s much, much more satisfactory when they are – the few books where she’s indulged in a way-to-the-side character’s guilt are not, on the whole, among my favorites.

My point being, Christie’s method is typically to hatch a murder scheme where the most obvious person – the will’s beneficiary, the secretly-blackmailed, the jealous husband – did the deed, but invented such a crafty plot that they are automatically ruled out from the start. Word to the wise: if you ever see a Christie character draw up a list of potential murder suspects, you can bet your bottom dollar the murderer is not on there. Or if they are, they are dismissed out of hand for some reason or another.

And if it is the most obvious person, they become, ironically, the least likely – because what kind of novel would that be, if the most obvious person was the murderer? A Christie novel, that’s what!

In fact, the culprit is often the very same person who pointed out the problem.

This is especially apparent in Christie’s short stories, but it’s a pattern that repeats elsewhere, too. I won’t go into specifics, but ten to one, Hercule Poirot (or, to a lesser extent, Miss Marple) is faced with his man (or, to a lesser extent, his woman – Christie didn’t discriminate, but I find her murderers are more often men) from first blush. I think this is because we have a subconscious belief that the person who seems invested in solving the murder, or robbery, or whatever it may be, would naturally not be the killer, or robber, or whatever – even if, as stated above, they have the strongest motive.

You might be thinking by now: Why give away all Christie’s tricks?

I admit, there is a certain pleasure in having figured out the notoriously hard-to-solve works of Christie’s before I’ve reached the end. I will say, to her credit, it is nearly impossible to guess the reason behind every clue that makes Poirot’s eyes go cat-like, or to explain away every odd circumstance, even if I can reliably guess the murderer by now.

However, I point out these formulas moreso as a fan than a critic. I have heard it said (i.e., on the backs of her books) that any would-be mystery writer should study Christie, and I have to say, agree. Her plots may be formulaic – I can pretty much nail down exactly when the second murder is going to occur, to a chapter – but when you read an Agatha Christie, it’s never really about who the murderer is, is it? It’s about the journey towards that destination: the scrap of paper in the fireplace, the clock that broke at half past three, the flash of a red kimono glimpsed at the end of the corridor. It’s about the wonderful interplay of all her beautifully drawn characters, many of whom fall in love just as often as they murder each other. Because if there’s one thing Agatha Christie loved more than a murder, it was a happy ending. After all, what could make one happier than nabbing a killer – other than a cold night, a hot cup of chocolate, and a cozy Christie to sink your teeth into?

***Expect a ranking someday, when I have the time and energy. Watch this space!***

Leave a comment